At Europe’s End

Martin Engels, moderator of the Reformed Alliance in Germany, reports on his visit to Idomeni, Greece.

On the way to Idomeni a stork lands on a lamppost on the side of the empty highway, which leads us from Thessaloniki to the small village near the border between Greece and Macedonia. It is the season when birds migrate across Greece to the North.

No one else migrates along this route anymore. In the last 20 days not a single train has used the single track that connects Greece to the north and trucks are diverted from the motorway because the border crossing near Idomeni is closed. We read and hear that refugees are blocking the route.

The first tents appear near the last gas station before the border crossing. Colorful camping tents and the larger white tents of the UNHCR stand on the resting area. Someone has written on a piece of cardboard, “We will not leave until you find a solution.” People carrying heavy bags and others with empty hands walk along the emergency lane. On the opposite lane every now and then a taxi drives by. Much money is to be made with the distress of people as we will be told later.

Idomeni sits at the foot of snow-covered mountains, an insignificant village, which has become a symbol of the misery of people seeking refuge and of the misguided European policy of asylum. Hundreds of tents are scattered on both sides of the train tracks. One can see from afar that between the tents people are making fire to cook food. Children, youth and old people gather twigs and branches, everything that is combustible.

In the midst of the camp I notice the numerous children jumping around. With smiling faces they wave at me, playing with everything they find—gravel, wooden crates or a concrete pipe from a construction site. Potatoes and onions are being distributed in bags. Hundreds stand in two queues. It is crowded and hot, and the people want food. The small truck is almost empty and, just from watching, I notice how tense the situation is. A small container is being used as a kitchen to provide meals every day, at least for a few. As I am looking inside the kitchen, I notice a little girl outside sitting in the dirt and eating a raw potato after peeling it with her teeth.

Our hosts from the Greek Evangelical Church guide us through the camp. This camp with an estimated 15,000 people does not exist officially. A police bus secures the last stretch of train tracks before the border; a helicopter of the fire brigade hovers over the camp; here nothing is organized. Those who happen to be here offer their help. It impresses me how active this small church is. Every day they distribute thousands of meals. One has installed a free Internet connection and provides electricity to help the refugees keep in touch with their families. Before that, vendors were taking five euros just for recharging a smartphone. An illuminated panel fixed to the roof of the container is used by the UNHCR to pass on information, inside the Doctors without Borders store their prescription drugs are next to rubber boots in small sizes for children.

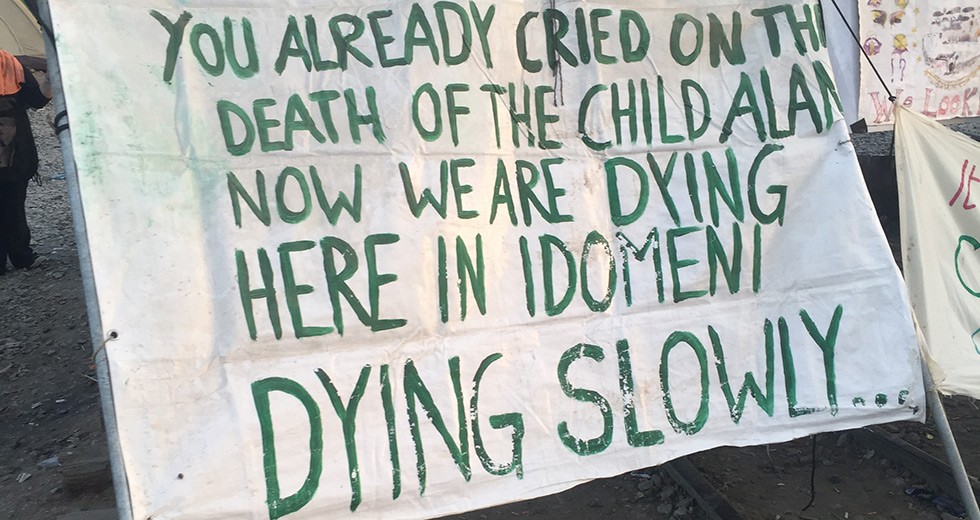

The people in the camp kindly greet us. They want to tell us their story and let me understand that I should look and tell at home what I have seen, such as the mobile toilet from which the overflowing liquid runs close by a tent where a one-year-old child is asleep. I see things that I would never have thought were possible in Europe.

I look across the field, where a woman washes a pan in a puddle. I am told that she is one of the richer persons because she owns a pan. Our guide points to the large Casino and Flamingo Hotel in the distance, maybe 10 kilometers away, behind the border fence. It is a bizarre scene, a caricature of the blatant injustice.

A pink sweater is hanging to dry on the barbed wire in front of a tank demonstrating the power of the Macedonian army.

The people here are in a dead end street. The border is closed. The only official possibility to apply for asylum would be by Skype, but the Greek authorities cannot deal with this, nor are the technical means available. Thus they have no access to this human right.

Yet, in this hopeless situation we meet UNHCR staff, who are still optimistic and do not want to give up hope that a solution will be found, and also children who play and want to make fun with us.

The fact that a refugee camp like the camp of Idomeni exists in Europe is outrageous. The fact that people who seek asylum must live under conditions far below the minimum standard of living on our rich continent puts Europe to shame and must arouse us as the Church of Jesus Christ!

- Read this post in German

- Part II: Torn Reality (German)

- Part III: Rich Hands (German)

World Communion of Reformed Churches

World Communion of Reformed Churches